Juliet Conway | 20 March 2017

While in a group of 8 PhD students recently, I discovered just how bad we all are at summarising our research. Our topics, on which each of us could wax lyrical for hours, cannot fit into a succinct summary, not at least without using several 5-syllable words. I am equally guilty of this. I try to get around the issue with a one-word answer. ‘What do I study?’: ‘Flirting’. It works, and usually gets a laugh or a politely bemused look. But if you ask me to extrapolate you’ll probably regret it. My arguments, which would (hopefully) sound eloquent and comprehensive in 100,000 words, become jumbled, convoluted and frankly indecipherable when squeezed into a few sentences. The questioner’s eyes start to glaze at the word ‘dichotomy’ and as I try falteringly to explain how flirts use intentional ambiguity to undermine notions of authority, I know I’ve already lost them.

This is all fine if most of your friends are PhD students, but if, like mine, the majority of your friends haven’t read much since the last Harry Potter book came out, how can you explain the general concepts of your argument in a way that their attention might be held until the end of your answer?

When I used to tutor secondary school students I had one boy so sullen that our sessions consisted primarily of awkward silences and monosyllabic answers, punctuated by his regular reminders that he hated English, didn’t want to be here and that he still hadn’t opened his course text, The Great Gatsby. After five weeks of this, I cracked. For next week, find six examples of quotations in which one of the characters is acting like an asshole, I told him. Then write me a sentence on each, saying exactly how much you despise them. ‘Can I use bad words’ he asked. I said only if he actually read the book and didn’t just watch the movie.

Bizarrely it worked. He actually read the book. Eventually he wrote an excellent essay on whether or not Gatsby is the most unlikeable character he’s ever encountered, which, once I’d removed the less school-friendly words, got him his first English A Grade. I realise getting someone to trash a book seems counterintuitive for an English Literature student, but at least he actually read it. He even asked me if Fitzgerald had written anything else. Every time I feel myself getting too precious about my research I remember this incident. This guy could understand The Great Gatsby perfectly well after he started, he just didn’t have that initial way to get into it, or the motivation to try.

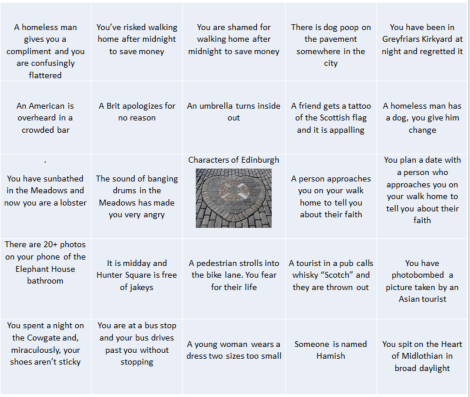

When I found this Jane Austen bingo card online I immediately saved it to my computer. Even though I’m not currently tutoring, when I see an example of an explanation technique I think is clever, I store it up. You never know when your next encounter with a sullen, literature-hater might occur. The bingo card is simple, funny and irreverent. But it’s also not inaccurate. In a slightly mocking way, each box does sum up a small aspect of Austen’s works, and, when brought together, reveals key themes, issues and plots commonly used in her novels. If I was teaching Austen to teenagers again this sort of interactive way in would be golden.

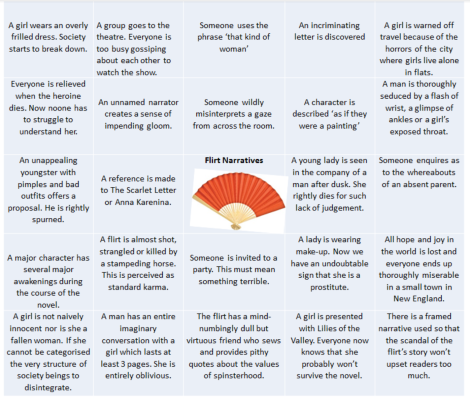

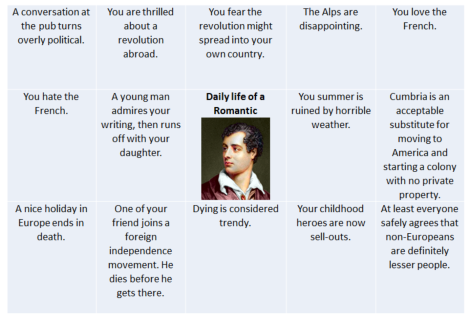

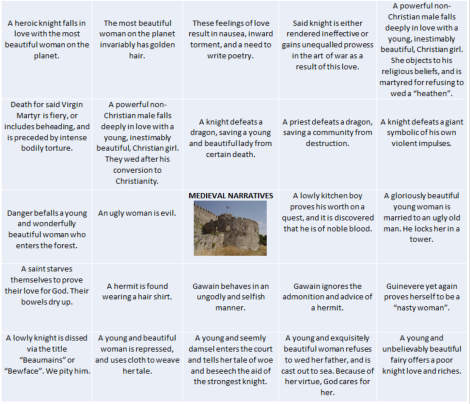

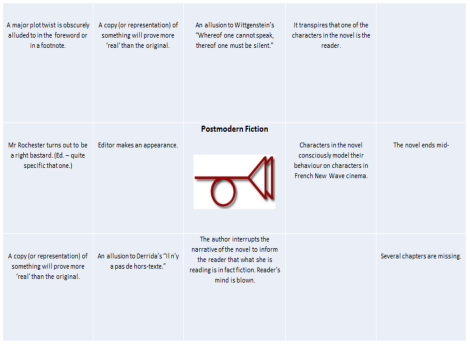

It made me wonder, could bingo cards be used effectively to work through and communicate our PhD projects? I started by making one for my own research on flirt narratives, and then, thanks to some excellent pals and their willingness to leave their intellectual vocabulary behind for half an hour, gathered some other examples.

Flirt Narratives: Juliet Conway

The Life of a Romantic: Valentina Paz Aparicio

Medieval Narratives: Anna Mackay

Postmodern Fiction: Richard Elliott

Creative Writing in Edinburgh: Kelly Pierce

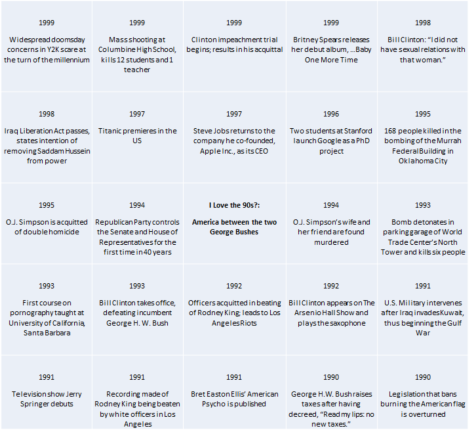

90s America: Niki Holzapfel

What are the merits of this seemingly nonsense exercise? Can bingo cards really offer a valuable way into academia? I think so. Making my card made me clarify the overarching goals of my research – in a way I never quite manage in convoluted notes. It made me step back and consider some important questions in a straightforward way. What are the cliches, what are the recurring themes? Why did that weird conversation just happen in three different books? It made me cut the waffle and any attempts to use impressive intellectual sounding words and actually get to the point. I realised that the word ‘dichotomy’ doesn’t belong on a bingo card.

In academia, imposter syndrome is a very real phenomenon. It’s very easy to envisage yourself as the dense one of the department and write off other people’s projects as something too abstract or theoretical or complicated to ever understand. Looking at other people’s projects summed up on a bingo card gets rid of any of this intellectual inferiority. It’s an easy way to get a conversation started and welcomes questions, without the fear of sounding stupid. I tested a few of them on my very non-literary friends and it was the first time we’ve ever managed a discussion on literary genres – never mind the ins and outs of postmodernism.

When research funding comes with demands for ‘impact’, being able to have fun with our research ideas and communicate them in clear and accessible formats is more and more essential. And perhaps for us PhD students, consciously boiling down our research ideas is a good way to check that we really know what we’re saying and not simply hiding behind an intellectual sounding vocabulary.

About Juliet

I’m an Edinburgh girl through and through and am currently in my seventh year at the University. I have just started a PhD researching the flirt figure in American fiction from 1870-1920, which is about as ditzy as it sounds. When I’m not examining how-to flirt guides, I love looking at how academic ideas can be translated for audiences outside of University.